May-Thurner Syndrome

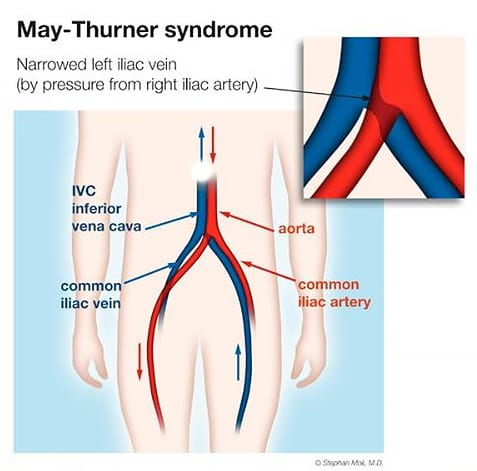

The most common of the four, May-Thurner Syndrome is the compression of the left iliac vein by the right iliac artery. The left iliac vein carries blood from the left leg to the heart, and the right iliac artery sends blood to the right leg. This can lead to symptoms of pain, pressure, and pooling of blood – on the left side of the pelvis, leg, and/or abdomen (if collateral veins are present, pain may not exclusively be on the left side). Some may feel it in their back as well, and some experience leg swelling. Fatigue is another common symptom.

In some cases when blood pools in the legs, May-Thurner Syndrome can develop into Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). However, it is important to acknowledge that not all patients with May-Thurner necessarily have or will develop DVT, and not everyone who experiences DVT has May-Thurner. Additionally, not everyone who has an iliac vein compression is symptomatic.

The compression occurs near the belly button; since a significant compression inhibits blood flow up towards the heart, the vein becomes dilated below the compression. Secondary to May-Thurner, patients may have pelvic congestion (female) or males may have enlarged veins by the left testicle.

Diagnostic Imaging

CT scans and MRIs may detect a congested iliac vein, but Doppler ultrasounds and Venograms are the most effective modes of testing.

A Doppler ultrasound measures blood flow and is simply placed over the abdomen, pelvis, or legs.

A Venogram involves using an X-ray to visualize vessels and blood flow via a catheter, which goes in through a vein in the thigh or neck. Further, an Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) can be used during a Venogram to measure from the inside of a vein to detect the level of compression. A Venogram is generally performed under partial sedation so that the patient does not feel pain during the procedure.

Populations Commonly Affected

May-Thurner Syndrome affects females and males among a wide age range, although females are more commonly affected, especially those between 20 and 40 years of age.

Treatments

The following treatments would be provided by a Vascular Surgeon.

- Venoplasty – A balloon is temporarily inserted (for about a minute) into the vein to expand it and is then removed. In some cases, this procedure may be sufficient for long-term relief, but often the effects are temporary.

- Iliac vein stenting – A stent placed in the left iliac vein at the location of the compression is the first-line treatment beyond venoplasty. The stent is intended to be permanent, but could be removed if the stent migrated out of place, which is very uncommon. Especially if collateral veins are present, it may take months to experience resolution of symptoms. A blood thinner medication may be prescribed for the first few months after placement.

- Bypass – A piece of tissue from the elsewhere in the patient’s body or from a donor is used to construct a new route around the compressed part of the vein to enable proper blood flow.

- IVC filter – For those with DVT as well, an Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) filter might be recommended. The filter is placed in the IVC – the major vessel that carries blood to the heart – in order to trap blood clots so they do not reach the lungs.

Nutcracker Syndrome

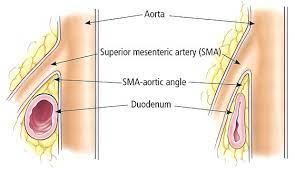

Nutcracker Syndrome is considered to be rare, though it is likely more common than is reported. The abdominal aorta and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) compress the left renal vein due to a narrow angle between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery. Some people have what’s known as “Nutcracker Phenomenon” – the anatomy of a decreased SMA-aorta angle, without being symptomatic.

The left renal vein drains into the inferior vena cava – the main vessel carrying blood to the heart. With blood flow being inhibited, fatigue is a common symptom. Pressure and pain in the left flank are hallmark symptoms, and blood in the urine (deriving from the kidney) can also be present. As the left gonadal vein drains into the left renal vein, pelvic congestion in females or varicoceles in males can occur.

Diagnostic Imaging

CT or MRI can be used to detect a shortened angle between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery.

Venogram and Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) measure blood flow and vein compression.

Populations Commonly Affected

Females in their teens and 20s to 40s are regarded as the most common patient population. Yet, some studies suggest that females and males may be affected at pretty similar rates. It also tends to affect those who are tall and thin because of a lower fat presence in the abdomen.

Treatments

The first two treatments would be performed by a Vascular Surgeon, while the last would be done by a specialist experienced with the surgery.

- Left renal vein transposition – This surgery reattaches the left renal vein to the inferior vena cava at a different location. As a result, this enables the renal vein to avoid moving between the aorta and SMA. The surgery may be open or laparoscopic.

- Left renal vein stenting – A stent is placed to expand the vein in order to restore proper blood flow. However, many physicians prefer the vein transposition surgery because the left renal vein is still sandwiched in between the aorta and SMA with a stent.

- Renal autotransplant surgery – Typically reserved for more severe cases, this involves the transplant of the patient’s own left kidney to a new location in order to free the left renal vein from constriction. Recovery from the surgery can take months.

Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Syndrome

SMA Syndrome, alternatively known as Wilkie’s Syndrome, is defined by the compression of the upper part of the small intestines by the SMA and abdominal aorta. The SMA provides the blood supply to the small intestines, and compression of the SMA against the AA can prevent duodenal contents from draining into the jejunum (upper small intestine). Consequently, patients become malnourished and experience weight loss.

Pain from this compression can be debilitating, making it difficult to consume food and exacerbating the condition. Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms attributed to compression of the duodenum. With persistent weight loss, the angle between the SMA and aorta decreases, further aggravating the compression and intestinal obstruction. While SMA is rarer than Nutcracker Syndrome, some patients present with both as the two are characterized by this decreased SMA-aorta angle.

Diagnostic Imaging

CT can be used to show a narrowed angle of under 25 degrees between the SMA and aorta. CT angiography or MRI angiography are useful for visualizing the compression as well. Duodenography (an X-ray that images the duodenum) is another study that may be utilized.

Populations Commonly Affected

Patients in their teens and 20s seem to be most commonly affected, and more so in females. Similar to Nutcracker, people who are tall and thin are more predisposed.

Treatments

The treatments would be performed by specialists who treat SMA Syndrome.

- NJ feeding tube – A nasojejunal (NJ) feeding tube inserted from the nasal passage into the jejunum for nutritional consumption. This enables easier nourishment, and in some cases, is a sufficient treatment as weight gain can improve the SMA-aorta angle.

- Surgery – If more conservative management fails, laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy is a surgery to mobilize the duodenum that has high success.

Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome (MALS)

MALS, also known as Dunbar Syndrome, occurs when the median arcuate ligament in the lower part of the chest sits lower than normal and compresses the celiac artery, which supplies blood to the stomach, liver, and other digestive organs. Also, it can press against nerves around the artery. In turn, this compression slows blood flow to those organs and causes upper abdominal pain. The median arcuate ligament is an arc-shaped band of tissue in the chest.

Common symptoms include chest pain, upper abdominal pain and bloating, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. This can make it very difficult to eat sufficient meals and get proper nutrition, leading to weight loss. Since the median arcuate ligament connects the diaphragm, shortness of breath is another potential symptom.

Diagnostic Imaging

A Venogram or Doppler Ultrasound visualizes blood vessels and flow. CT or MRI can show the organs and surrounding structures involved.

Populations Commonly Affected

Females in their 20s to 40s are the most prevalent patient population, although females and males who are younger or older can also be affected.

Treatments

The treatment for MALS is release of the celiac artery by removal of parts of the median arcuate ligament and tissue that surrounds the artery. The surgery is open, laparoscopic, or endoscopic based on the physician’s judgment and expertise. A surgeon who specializes in MALS would perform the treatment.

Seeing Medical Providers for Diagnosis

One of the most distressing things is when you have symptoms, don’t know what condition you may have, and keep seeing doctors who are unable to find anything and diagnose you. When you have some idea of conditions you may possibly have, or the nature of the symptoms, it gets easier because you have a better idea of the right specialists to see. For instance, going to see a Vascular Surgeon or Interventional Radiologist, both of whom could perform a Venogram, from the start would make the process smoother. Furthermore, seeing someone who specializes in the vascular compression syndrome (or in all of them!) from the beginning would be optimal because this may avoid having to be referred elsewhere.

However, some insurance plans require patients to see a primary care physician first. If that is necessary, the best course of action is to try to find a primary care physician who is supportive, and if possible, has referred previous patients to a specialist for vascular compression syndromes. If the physician you’re seeing – whether a primary care doctor, vascular surgeon, etc. – is not listening to what you’re describing and taking your symptoms seriously, then you should see someone else who will. It is often difficult to find a medical provider that treats vascular compressions, but they are out there! The financial component which is cumbersome for some is another harsh reality; however, it is important for long-term health to have issues like these treated, especially if they are impacting quality of life.

Additionally, information is available on online resource and support groups for vascular compression syndromes, including some Facebook groups.